Indeed,

the example of chef Bernard Loiseau, who committed suicide in 2003 amid

speculation that his restaurant was about to lose its third star, is often

cited to demonstrate the hold the Red Guide has on chefs.

Photo by Getty Images.

But

some chefs see the patronage of Michelin as an unwelcome weight that prevents

them, they feel, from innovating and one which raises customer expectations to

unreasonable levels, where even the slightest imperfection is greeted with

incredulity.

Chef

Karen Keygnaert of Belgium’s A’Qi restaurant recently spoke to Munchies about

her desire to return her star because it “brings along a whole circus that’s

outdated. If there’s even a crease in the menu card or a crease in the

tablecloth, people soon end their sentence with: ‘I don’t think that belongs to

a star restaurant’... You lose the freedom to do what you want as a cook.”

The

only problem is, you can’t technically return a star. “You can agree with it or

you cannot, but you can’t give it back. That’s not an issue ... kind of an

urban myth,” said the Michelin Guide’s International Director Michael Ellis in

an interview with Vanity Fair in 2015. Keygnaert came up against a brick wall

trying to return hers: “It’s a very closed, absolutely not transparent

institute. You can’t even ask them for an explanation. You have no right to an

answer; they are untouchable,” she says, having written to Michelin and

received no reply.

Keygnaert

is not the first chef to ‘return’ her stars of course. Marco Pierre White famously

returned his three Michelin stars after becoming disillusioned with the

Michelin world and the pressures associated with it, questioning why inspectors

with inferior culinary knowledge to himself were judging him. In 2014, Julio

Biosca of Casa Julio, close to Valencia, returned his star, describing the

Michelin system as “burdensome,” while Skye Gyngell of London’s Petersham

Nurseries Cafe famously described a Michelin star as a “curse” after falling

foul of diners incensed about the restaurant's shabby chic aesthetic, despite

having been open for seven years before gaining its first star. She later

closed the restaurant.

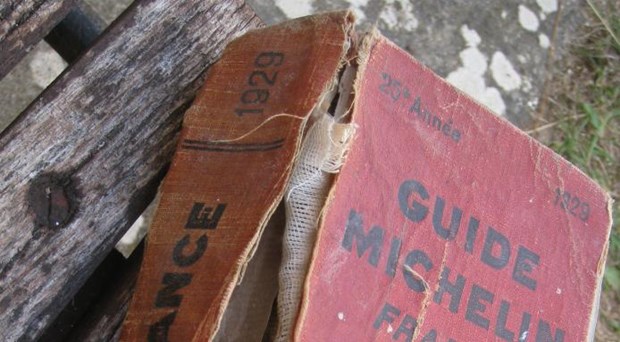

Photo by Trou/Wiki Commons.

And

then there’s Frederick Dhooge of 't Huis van Lede in East Flanders, Belgium,

who gave back his star in 2014, arguing that he should be free to cook fried

chicken if he wanted to and Le Lisita in Nimes, France, which decided to

relinquish its star in favour of a more relaxed brassiere style.

Chefs

willing to speak out are in the minority of course, and for many, a star, then

two, then three will still be the pinnacles of their careers, and can make the

difference between survival and closure.

Perhaps

there are some rides that are just too difficult to get off once you’re on.

By FDL