Sweet

flavours are inevitably associated with sugar. In scientific terms, sugar is

one or more molecules made up of carbon, hydrogen and oxygen. These may be

single molecules, as in the case of glucose or fructose, or combinations of

molecules: sucrose, for instance, consists of a glucose molecule and a fructose

molecule bonded together. I have a particular reason for referring to sucrose:

common table sugar, the sort normally used in cake and pastry making, is in

fact sucrose.

There

are many reasons why this kind of sugar has become so popular in cooking and

baking. First of all, it is widely available: sucrose, or common “sugar”, is

extracted from sugar cane and beet, which are easy to grow almost anywhere in

the world. Not surprisingly, its annual production amounts to 70 million tons.

Melting sugar:

Chemical reactions

Sucrose

is highly soluble: as much as 2000 grams of sucrose can be dissolved in one

litre of water! However, it is mainly due to the way it reacts that it has

become the protagonist of our sweetest recipes.

The

chemical reaction we are most familiar with is that of melting: sugar

decomposes at a temperature ranging between 184 and 186°C. This is a very

recent discovery we owe to a team of researchers in Illinois. Basically, when

we heat sucrose gently, this produces a phenomenon known as “apparent melting”.

In other words, sugar crystals do not actually melt but produce a proper

reaction called “inversion”. What really happens is that the two molecular

components of sugar – glucose and fructose – decompose. In their turn, they

give way to “caramelisation”, consisting of two phases.

Melting sugar

In

the first phase, the structure of sugar changes as the heat increases. We can

easily observe this for ourselves when we see sugar starting to “melt”. At this

point, the second phase kicks in: the additional increase in heat causes the

elimination of the water molecule. This produces a reaction called

“beta-elimination” which leads to the formation of hydroxymethylfurfural. The

substance darkens in colour and tastes more and more of caramel. If too much

heat is applied, nothing but carbon will remain, which means that our caramel

is well and truly burnt!

In

brief, that of heating sucrose may appear to be a banal operation but it can

offer us a series of interesting reactions. In particular, “inversion”, which

benefits from an acid pH, gives us “invert” sugars that are very hygroscopic:

this means they are able to absorb a high number of water molecules, which

makes them ideal for preparing soft sweets and desserts or, indeed, for any

recipe we wish to keep moist even when it has to be exposed to the air.

A tip for making soft

sweets and biscuits

We

can apply this principle to ordinary sugar to give our sweets a more or less

soft consistency, biscuits in particular.

Pumpkin biscuits

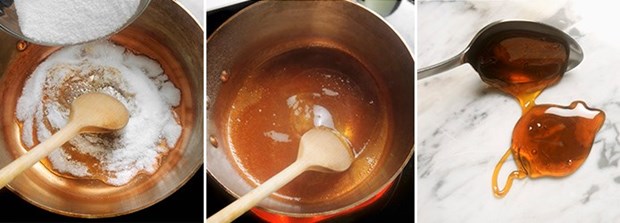

First

of all, we need some invert sugar which can even be home made using 200 grams

of sucrose, the juice of one large lemon and 140 grams of water. Place all

three ingredients in a small saucepan and slowly bring them to the boil over a

low heat, stirring constantly with a wooden spoon. Now, let the mixture simmer

for at least half an hour, stirring as little as possible. Finally, leave it to

cool and transfer the syrup to a jar, for use when needed.

You

can use it to prepare pumpkin biscuits for example. Grate 100 grams of pumpkin

and add it to 250 grams of flour, 1 egg, 50 grams of invert sugar, two

spoonfuls of sour cream and 30 grams of butter. Mix all the ingredients

thoroughly, roll out the mixture and use a biscuit cutter to obtain the shape

you require before arranging your biscuits on an oven tray. Bake for around 25

minutes in an oven preheated to 160°C. These delicious biscuits will always be

soft and moist thanks to the secrets of sugar!

By FDL