This

autumn, a global audience watched writer and chef Anthony Bourdain eat bun cha

with a sitting American president. In the same episode, Bourdain happily

patronized a middle-aged woman offering verbal abuse and “hot-tempered

noodles.”

The

episode raised eyebrows in a city both proud of its cuisine and worried about

the way the world views it.

Decades-old

concerns about the use of dyes, pesticides and preservatives in food vanished

into anxiety about the coarsening of the culture. While many dismissed those

worries as frivilous, they exposed a nostalgia for something lost.

During

the abyss of Vietnam’s struggles with French colonialism, pho, bun cha and

other street delicacies blossomed, providing succor to workers, intellectuals

and aristocrats alike. This opening invited a generation of energized young

writers to interpret the explosion of a culture thriving in chaos.

“Vu

Bang was the first of his contemporaries to create an integral and

comprehensive work on Hanoi’s cuisine,” claimed Ngo Van Gia, an expert on the

writer’s work. “So far, no one has surpassed him.”

Pioneering

literary critic Pham Xuan Nguyen describes his work as transformational: “Today

we read Vu Bang to mourn a time when eating wasn’t just a way to fill one’s

stomach. Eating was an art.”

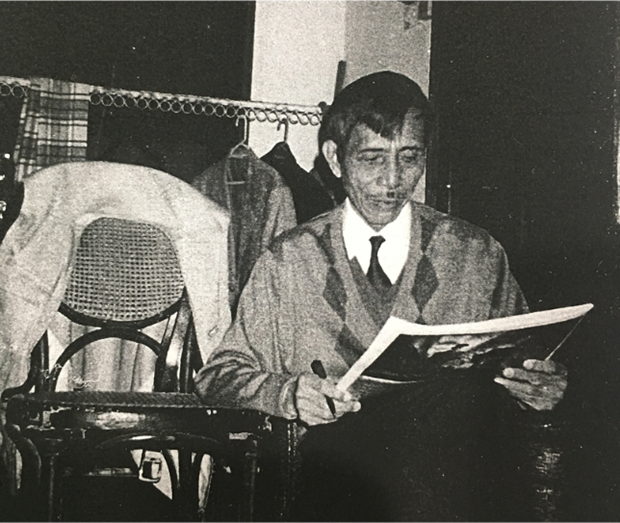

Portrait of Vu Bang.

From

opium to street food

Vu

Bang didn’t fall into food writing easily.

Bang

was born in 1913 into a Confucian family in the middle of the capital.

After

his father died young, his mother sold books to the French colonial authorities

and sent him to study at Lycee Albert Sarraut, a high school for the colonial

elite.

There,

Bang studied French literature and came to idolize contemporary journalists, so

much so that he dropped out of school to start writing.

Bang

published his first book at the tender age of 17, attracting respect, recognition

and wealth. The teenage literary star quickly developed a taste for women and

opium.

In

his 1944 book Rehab, Vu Bang recalled a younger version of himself who

preferred “death in vigor to life in disgrace.” He spent days and nights in

ecstasy, carousing with fellow writers, countless escorts and the beautiful

fellow addict he called his girlfriend.

The

death of a cherished aunt inspired Bang to get clean in a lowly asylum. Years

after rehab, he married a divorcee named Nguyen Thi Quy, who was seven years

his senior.

Quy

kept her addict husband sober on food. Whenever Bang felt a craving coming on,

she took him out to discover a new street dish.

More

than anything, though, she kept him happy at home.

The

couple’s only son, Vu Hoang Tuan (now 80), described Quy as an elegant

intellectual who quickly mastered the capitol’s cuisine.

“She

never revealed where she learned to cook,” he said. “Yet, she knew everyone’s

favorite and always insisted on cooking every aspect of a given dish herself.”

Tuan

credits his mother for teaching Bang everything he knew about food.

A despised spy

Scholars

say Bang spent two years offering intelligence to Communist revolutionaries in

Hanoi before the French withdrew in 1954.

With

the country split in two, Bang agreed to follow migrants south to Saigon before

the eruption of a bloody war.

The

writer turned spy believed he would spend just two years posing as a refugee, a

cover story that led many of his admirers in Hanoi to condemn him as

counter-revolutionary.

But

Bang’s assignment stretched into decades, keeping him from the food and woman

he loved.

In

1956, according to their son Tuan, Quy slipped into Saigon and spent a month

with her husband for the last time.

When

she arrived back home to Hanoi, the police were waiting for her.

“The

police asked a lot of questions and threatened her,” he said. “I remember her

responding in French: 'In life, there are many truths that cannot be told even

to family.'”

As

tensions flared, he remembers his mother calmly explaining that, under no

circumstances, would Bang betray the revolution.

Life

got harder for the family from that day forward.

Portrait of Vu Bang. Photo courtesy of Ngo Van Gia.

Delicacies of Hanoi

In

the two decades of exile that followed, Bang produced satirical comics,

articles and novels.

Rare

breezy days in Saigon conjured memories of autumn in Hanoi and “frugal family

dinners, which were far more delightful than soup filled with shark fin or

bird's nest.”

Pining

for dishes he would never taste again, Vu Bang wrote a series of essays that

stirred nostalgia among roughly a million northerners stuck in the Republic of

Vietnam.

Published

in 1960, Hanoi Delicacies described how a cuisine could live on in one’s memory.

“Even

if I was abducted for a thousand years, I would remain a Vietnamese longing for

the food in Hanoi,” he wrote.

The

book’s dedication reads: “To Quy, the cook that inspired this book, the friend

that brought every northern delicacy for me to relish.”

Seven

years after its publication, Quy died—scorned by a Hanoi struggling for

survival.

Revisiting Vu Bang

Vu

Bang believed that food in the capitol would never really change.

The

first chapter of Hanoi Delicacies

opens with Bang returning to a city devastated by French bombers in 1947.

“Though

you may find idiosyncrasies among its residents and houses, though streets may

have to be rebuilt, Hanoi’s eating habits remain the same,” he wrote.

Bang

described the city’s cuisine as an immutable function of the Red River Delta’s

seasons, courtship rituals and traditional farming practices—a gift to

humanity, on par with the works of Voltaire, Dickens and Shakespeare

In

spite of his deep passion for the food, he never got to eat in Hanoi again.

The

scholar Van Gia claims that after the war ended in 1975, Bang remained in Ho

Chi Minh City with a second wife and five children.

He

described Bang’s late life as “lonely, misunderstood and squalid”.

Seemingly

forgotten and unable to find employment even as a translator, Bang descended

back into his opium addiction and died in 1984.

His

brief obituary at the time made no mention of his writing.

In

the year 2000, Van Gia published a compilation of Bang’s work that confirmed he

had worked on behalf of the revolution as an undercover agent. Seven years

later, the Vietnamese government posthumously awarded him the National

Literature Prize.

The

award prompted Van Gia to publicly suggest the capitol name a street after the

writer. Sadly, it has yet to do so.

For

the next few weeks, we will revisit Hanoi

Delicacies, hitting alleyways and markets in pursuit of the mission Bang

set forth in the book’s opening pages:

“I want to interpret and explain Hanoi’s delicacies

– mouthfuls of a nation’s essence that elicit pride and excitement in

Vietnamese and make them proud to have been born here.”

Writer:

Quynh Trang, Nhung Nguyen/VnExpress